On August 2nd, an officer named Mark Royko with The Ohio State Highway Patrol went to Ohio State Penitentiary, had Siddique Abdullah Hasan pulled out of his cell and tried to question him about Sep 9. See Hasan’s summary of the conversation below.

On August 2nd, an officer named Mark Royko with The Ohio State Highway Patrol went to Ohio State Penitentiary, had Siddique Abdullah Hasan pulled out of his cell and tried to question him about Sep 9. See Hasan’s summary of the conversation below.

This officer used some pretty ridiculous terror-baiting language, so we are going to use this opportunity to remind everyone about some basic principles of security culture and anti-repression.

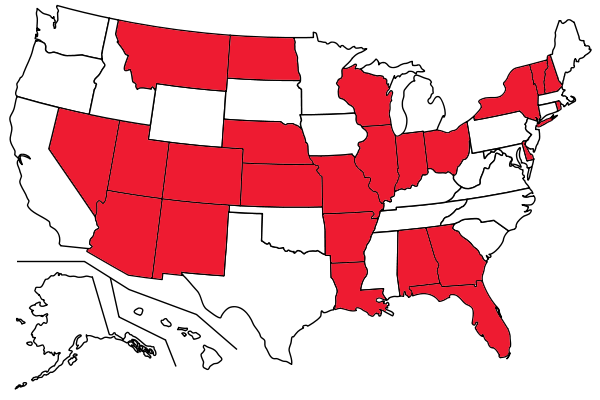

1. Do not talk to law enforcement. In the example below, Hasan was more open than we would advise anyone to be. As soon as you know the person you are talking to is a cop or a fed, walk away slowly. If they stop you, ask if you’re being detained. If they say yes, ask if you’re under arrest. In these states you’re obligated to by to give your name and show ID. In other states, if you’re driving a car or carrying a gun under an open or conceal carry permit, you’ll also need to show your ID. If you refuse to show your ID the cops, they might make up some “reasonable suspicion” pretext to arrest you, and the trouble of getting arrested and then getting it thrown out in court is maybe not worth it.

States (colored red) in which Stop and Identify statutes are in effect as of February 20th, 2013.

The cops can and do violate people’s rights all the damn time, and if you don’t want them to escalate and get violent with you, you might have to let them, just make sure you’re vocally asserting your rights (ideally before witnesses with cameras) while they trample them.

If they ask to search you say “no” out loud but do not physically resist if they search you anyway. Say “i do not consent to this search” out loud. If they arrest you, do not talk. Remain silent and assert your right to a lawyer. Follow basic ACLU know your rights protocol.

2. Tell people. Once the police have left, write down notes describing the encounter as soon as possible. If you can, get names and badge numbers of the officers. Tell anyone you’re organizing with. Email us at PrisonerResistance@gmail.com. Call IWOC Kansas City at 816-866-3808 or email iwoc@riseup.net. The more people know about law enforcement snooping around, the more safe we all are.

3. Practice good security culture. Cops don’t need to tell you they are cops. They can go undercover and infiltrate your group. This is not reason to get paranoid or stop organizing, but it is reason to be cautious. Developing habits of caution and awareness in radical communities is called practicing good security culture. The basic level of this is: don’t talk about things (especially important or illegal things) to people who don’t need to know, do not let people pressure you, and only plan actions with people who you trust.

For a lot more information on security culture see: http://www.crimethinc.com/texts/atoz/security.php

For more about identifying infiltrators and avoiding entrapment see: http://burningbooksbuffalo.com/products/profiles-of-provocateurs-recent-case-studies-warning-signs-practical-advice

4. Understand Counter-Insurgency. Beyond security culture, we need to pro-actively respond to repression and recognize that repression and counter-insurgency (ie: countering our activities) is already going on all the time, it is built into the fabric of our society today. Awareness is an important step. Some friends put together a great workshop on the subject. You can read the outline here or watch a video of them presenting it at a conference (here’s part 2 of video).

5. Prepare to defend yourself. It is a myth that attention from law enforcement comes when activists do things that are wrong or illegal, the reality is that law enforcement comes after us when we do things that are effective. If we want to be effective, we need to be prepared to defend ourselves against repression. Two of the bigger things the state wants to do to effective organizers is summon us to testify before a grand jury and charge us with crimes.

grandjuryresistance.org has a lot more information about grand juries. The basics: they might lock you up for refusing to talk, but it is important that you refuse to talk anyway. Snitching puts others in danger and does not really protect you. We support those who resist.

tiltedscalescollective.org has a lot of great info and strategic thinking about defending yourself against criminal charges, including this handy printable guide.

6. You are never alone. The National Lawyer’s Guild has endorsed the Sep 9 strike, the organizers are well connected with some of the best political prisoner support and movement defense people from all over the country. State repression is scary and it sucks to be targeted, but there are very experienced people close to this movement who will have our backs if law enforcement tries to come down on us.

Okay, now that you understand all of that, here’s what happened to Hasan two days ago:

A revolutionary salute,

This morning, it was something after 9:00, I was called out of my cell and told that somebody in the cage wanted to see me. I had no knowledge of who it was and the officers who was bringing me out had no knowledge who it was.

When I went out to the cage a few minutes afterwards, someone from the Ohio State Highway Patrol came to see me. He introduced himself as Mike Royko, he spelled it R-O-Y-K-O. He said that he had cases here from Youngstown, Trumbull Correctional Institution, as well as Ashtabula County.

He wanted to know my name, what I was in prison for, and I told him, you know, “Cut the game, I mean that’s not why you came out here. I’m sure you did all that investigation before you came out here to see me.” Then he went on to say that he heard that I was supposed to be involved in some kind of national militant movement to blow up buildings, to harm people, and I said, “Somebody must be sending you on a wild goose chase, because there’s no such thing that’s actually happened.”

If it’s coming from a prisoner, usually prisoners find themselves in a maximum security or supermax prison and they want to get out and they provide fictitious information to the prison authorities as a way to receive some type of leniency. When I’m telling y’all this information, if he or some of his people, or some people who like him, or others in prison in general, found out that I did this they are going to try to harm me and that’s the game some prisoners play.

If it came not from a prisoner, I can’t really speculate as to why that’s going on. But I clearly explained to him that, you know, I am involved in various movements, because that was one of the questions he posed to me—am I involved in any various movements or groups? I said, yes, I’m involved in Black Lives Matter, the Free Ohio Movement, and various different movements. People call on me to speak on radio programs and speak on college campuses about the quality of injustice that goes on behind enemy lines—police abuse, mass shootings, the killing of unarmed Black men, the list goes on and on and on. And that was the nature of our communication.

But before then he asked me the question, could he record what I’m saying. I said, “You do whatever you want to do. Because if you want to know what I’m saying, you can actually listen to my phone calls or read my mail.” It’s easy to read my mail. All you’ve got to do—the Warden can get permission from central office to open my mail and there’s nothing illegal about doing that. With regard to my phone calls, actually all phone calls in the State of Ohio are being recorded. And the only ones that are not being recorded is someone who is fortunate enough to have a cell phone in their possession. I don’t have that luxury so anything I say is actually on the phone.

But basically, what I tried to explain to them, which is truth, is that I’m involved in no radical movement that—not to my knowledge, unless someone is involved in some radicalism that I’m not aware—that I speak for myself or, if I speak, I’m speaking from a group base and everything that I’m involved in is peaceful movement trying to bring about revolutionary changes, and trying to bring about better conditions for prisoners, and trying to bring about emancipation and freedom from the case that I was erroneously convicted of, as a result of the Lucasville Uprising.

So that was the extend of our conversation, because I didn’t want to have no long conversation. I just told him, continue to listen to my phone calls, continue to read my mail, and exactly what I’m telling you, if you come to find out something otherwise, then you can come back and you can throw it in my face. Otherwise not, and we have nothing else further to talk about really. And that conversation happened about nine-something this morning.