From Waging Nonviolence

Along with Support Prisoner Resistance and the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee, or IWOC, of the IWW labor union, FAM issued a call to action earlier this summer, with an estimated 40 prisons in 24 states expected to participate. Much like the inmates who took over New York’s infamous correctional facility in 1971, today’s prisoners are fighting against the conditions of their imprisonment, especially the conditions under which they are forced to work, which many describe as slavery.

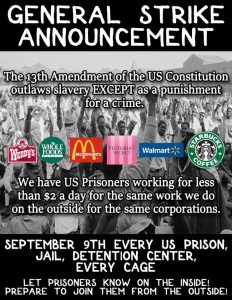

Although some states allow prisoners to get paid for their labor, the pay is often less than a dollar per hour, and sometimes absolutely nothing. Half of those wages, in federal institutions at least, are withheld for room and board, victim’s programs and family support. Whatever remains goes toward buying the necessary commissary items for making life in prison tolerable. Essentials like toilet paper, deodorant, menstrual products and laundry detergent can each cost multiple days’ wages.

Meanwhile, America’s prisons constitute a multi-billion dollar industry. UNICOR, also known as the Federal Prison Industries, reported net sales from inmate-made products and services of $472 million in 2015, and this is only for federal institutions. Federal and state prisons combined are estimated to produce at least $2 billion in goods and services.

In private prisons, there have even been reports of prison personnel selling inmate-made goods for personal profit. However, privately run facilities are facing increased scrutiny, as the Department of Justice recently announced it will no longer contract with private prison companies, and the Department of Homeland Security — which oversees immigration — is considering doing the same.

Inmates perform essential jobs like running recycling plants in Wisconsin, to fighting fires in California and Georgia. They also participate in a modern-day version of convict leasing, making uniforms for McDonald’s, running call centers for AT&T and even preparing artisanal cheeses sold at Whole Foods.

“We make products for every type of business you can think of,” said Ray, who is being held in the St. Clair Correctional Facility in Springville, Alabama, which was ranked one of the deadliest prisons in the nation just two years ago, due to overcrowding and an indifferent warden. “[The businesses involved] understand that this is an operation of slavery and everyone is exploiting the free labor out of the prisons.”

In addition to generating revenue, the labor of inmates is essential to keeping the prisons themselves running. Inmates deliver mail, prepare food and do laundry. But, according to Support Prisoner Resistance and IWOC organizer Ben Turk, this is precisely why prison work strikes can have a significant impact on the state.

“Work stoppages cost the Department of Corrections a lot of money in overtime because guards and prison staff have to do jobs prisoners would otherwise be doing,” Turk said, who has been involved in prison abolition since at least 2011.

Both Turk and Ray spoke about how actions often spread to other prisons. The 2010 Georgia work strike, after all, is what inspired Ray to start FAM in 2013. Lasting just under a week, at the time, it was the largest prison work strike to date, involving thousands of prisoners and nearly a dozen facilities. Inmates were seeking better educational opportunities, improved access to medical care and higher wages.”

Work stoppages and hunger strikes don’t often end in prisoners’ demands being met, but they do often inspire other prisoner’s to do something.

“[Prisoner strikes] are generally not successful at getting the specific demands,” Turk explained. “But they are very successful at inspiring other prisoners, and also building awareness and creating some of the cultural shifts that are necessary to get past these institutions of slavery and torture in America.”

The work of organizing these stoppages in a single prison — let alone across multiple facilities in two dozen states — is extremely challenging. Retaliation from prison officials can result in being stripped of any privileges or being locked up in solitary confinement. Meanwhile, communications are monitored by guards, unless prisoners are able to access a cell phone.

Siddique Abdullah Hasan, who is part of FAM sister organization the Free Ohio Movement and is an organizer of the September 9 work strike, has already been charged as a security threat — a catch-all charge that can be used to justify locking prisoners in solitary confinement. He will spend 30 days in solitary confinement at Youngstown’s Ohio State Penitentiary, stripped of his personal belongings, and denied access to email and other forms of communication.

Ray is no stranger to the repercussions of prison organizing. Back in 2013, FAM members started posting videos depicting the conditions of their prisons — the poorly maintained buildings, the food provided by the kitchens, the overcrowding of their facilities. They also started organizing work strikes in several Alabama facilities, following the example set by Georgia prisoners back in 2010. Eventually, Ray was put in solitary confinement as punishment for his involvement.

“It’s what they call soft touch or hands-off torture. It’s a small cell, it’s filthy,” Ray said. “It’s hell. I mean it’s literal hell, and they use it to torture people.”

Ray sees the forced labor of prisoners — running the prison itself, providing services to the state and being rented out to for-profit corporations — as not simply an unjust condition with roots in slavery, but the direct continuation of those practices.

“We were told and taught that the 13th amendment abolished slavery,” Ray said. “But the 13th amendment never abolished slavery. What it did was nationalize it.”

This is not hyperbole. The 13th amendment, indeed, makes it clear that slavery — despite being an unlawful practice among private citizens — is permissible “as a punishment for crime.”

Prisoners organizing against their forced labor, or any of the conditions of their confinement, must contend with a high level of monitoring by the state. Any mail or other communications with the outside world are subject to the scrutiny of prison officials.

“They gonna read all of our mail, just plain and simple,” Ray explained, especially if prison officials know a hunger strike or work stoppage is being planned.

However, there is also a reality that in severely overcrowded prisons, like many of the facilities in Alabama, guards and prison officials simply cannot keep up with what prisoners are doing.

“The Alabama prison system is the most overcrowded and understaffed at the same time,” Ray said. “So, literally, they don’t have enough officers to monitor our every conversation, our every move.”

In some states, it is easier to get cell phones into prisons, allowing inmates to coordinate activities unmonitored, as well as connect with loved ones, and share photos and videos on social media about their living conditions.

“Those states will probably be able to be more effective. That’s what worked in Georgia and Alabama,” Turk said, referring to the 2010 Georgia work strike and multiple work strikes that have happened in Alabama, often organized by FAM.

While those demands were never met, both Turk and Ray credit them with starting other work stoppages and hunger strikes, including the Alabama work stoppages that ultimately landed Ray in solitary confinement.

All that goes to show the power of cell phones, both in terms of coordinating between prisons and posting videos to social media.

“The most effective thing we do is we use social media,” Ray said. “We do our own videos, and we use the social media platforms to put those videos out.”

For that reason, he doesn’t see cell phones as mere contraband. “These are necessities to stay alive.”

As an organizer on the outside, Turk spoke about navigating the difficulties of getting information in advance of an action.

“It’s almost second nature for me to be able to respond to events as they happen on the inside,” he said, noting that oftentimes he may have an idea of when an action will start, and which prisons will be involved, but the specifics can rarely be confirmed.

Nevertheless, Turk is at the ready to coordinate banner drops in high-traffic parts of town; noise protests, where protesters gather outside a prison or jail and make as much noise as possible in order to let the inmates know they have support on the outside; and call-ins, to, for example, have a prisoner released from solitary confinement. He also fields questions from the press and arranges any legal support prisoners may need.

“Just a visit from a lawyer can go a long way toward checking the retaliatory efforts of the prison authorities,” Turk said.

And Turk, of course, isn’t alone in this work. Groups like The Ordinary People Society, which does a broad array of advocacy and support work around mass incarceration, are also supporting the call for the strike from the outside.

How the strike will unfold, whether it will reach national proportions for a significant length of time, and what will come of it are questions even the prisoners can’t answer. What is clear, however, is that they are fighting against an exploitative labor practice, and the demands are up to the organizers in each facility taking part.

While prisoners face incredible barriers to organizing, Turk and Ray, and many others like them, are — with each conversation, protest and day of resistance — incrementally slowing down the profit motive that drives the prison system.

For as slow as the progress may seem, Ray has a surprisingly practical approach. “September 9 is simply the next date on the calendar that we are going to continue to push our movement forward,” he said, because ultimately “we’re trying to dismantle the system.”