A nationwide prison strike planned Friday has Florida’s jails and state prisons on high alert through the weekend, bracing for possible upheavals by inmates protesting what they say is inhumane and violent treatment.

Already, a revolt at Holmes Correctional in Florida’s Panhandle on Wednesday night, involving more than 400 inmates, caused damage to nearly every dorm during an uprising that lasted into the early morning. No one was seriously injured, but the department is concerned that the disturbance might be a harbinger of what’s to come.

Florida’s prison system, the third-largest in the country, has been dangerously understaffed for nearly a year, and several sieges have occurred in recent weeks. To further exacerbate tensions, many inmates have been in forced confinement in their dorms, allowed out only to eat because there isn’t even enough staff to guard them during outside recreation.

Over the past two years, the Miami Herald has published a series of stories documenting the brutal or unexplained deaths of inmates in Florida prisons, a record number of use-of-force incidents and corruption by guards and top officers.

In recent weeks, the department has had disturbances at Jackson Correctional, Gulf Correctional, Franklin Correctional and Okaloosa CI. All of them, like Holmes, are located in Region 1, in the Panhandle. And a corrections officer was stabbed during a melee at Columbia CI in April.

“It’s very hot in those dorms and when you can’t get any rec, the inmates start causing problems,’’ said a veteran corrections officer at Holmes, who would not allow his name to be used for fear of reprisals.

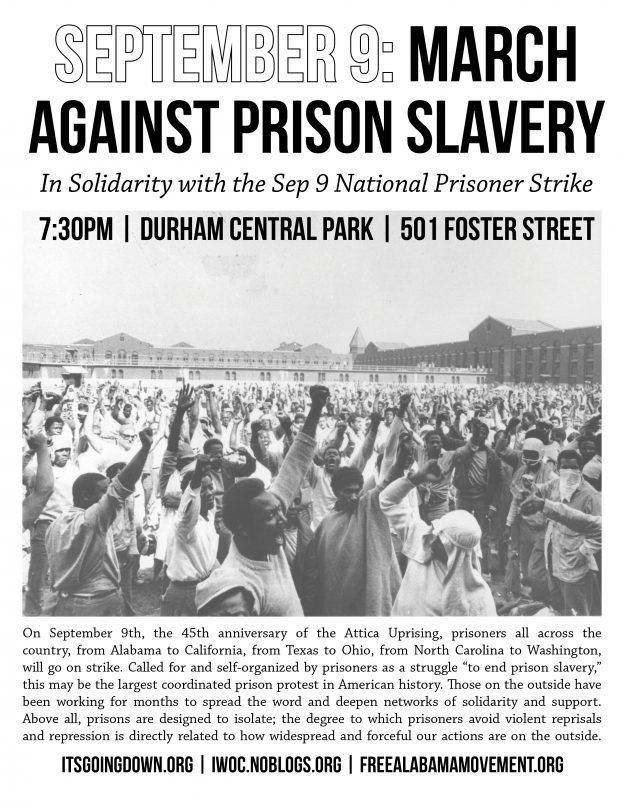

The loosely organized national strike, a grassroots effort, comes on the 45th anniversary of the prison riots at Attica, the 1971 prison siege near Buffalo, New York, considered the largest prison rebellion in U.S. history. Over 40 people died when inmates took control of the facility for four days, protesting racism, officer beatings, rancid food, no rehabilitation programs and forced labor.

Phillip A. Ruiz, an organizer for the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee, one of the groups spearheading the Friday demonstrations, said conditions in America’s prisons aren’t that different from those at Attica 45 years ago.

“They are participating in work stoppages, hunger strikes and sit-ins in protest of long-term isolation, inadequate healthcare, overcrowding, violent attacks and slave labor,’’ said Ruiz, whose committee is part of the Industrial Workers of the World, an international labor union whose membership peaked a century ago.

Ruiz said organizers are emphasizing that the protests will be nonviolent. Florida corrections officers have nevertheless been briefed and are prepared to work all weekend in case there are uprisings.

Of the disturbances in Florida, the riot at Holmes involved the most inmates so far — more than 400 of the 1,100 men incarcerated there — and was spread across the compound.

Officers interviewed by the Herald said that Wednesday’s rebellion began in B Dorm about 6 p.m. One officer, stationed in a control center (called “the bubble”), was in charge of nearly 150 inmates. The prisoners put blankets and sheets over the windows of the bubble then proceeded to smash cameras, ransack the dorm and then began tearing away the ceiling and crawling in the attic, possibly trying to escape.

Officers from five other prisons were called in, as well as special RRTs (Rapid Response Teams) trained to handle riots. Though some officers were armed, no shots were fired, sources said.

“We would get one dorm under control and then it would start in another dorm. It was every dorm, as if it was planned,” the Holmes officer said.

It took until 4 a.m. to bring the compound under control, he said. Officers were able to restrain many inmates after setting off canisters of chemicals, making it hard for the prisoners to breathe, the officer said.

The compound in Bonifay, a town of just more than 4,000 that is bisected by Interstate 10, was still on lockdown Thursday, according to a statement released by FDC shortly after noon. One inmate was injured but no corrections officers were hurt, the statement said.

The department did not say when the uprising happened, what precipitated it, how long it took to bring it under control or how much damage occurred.

Photographs leaked to the Herald show damage to ceilings, floors, beds, walls, cameras and doors. The inmates were transported to other prisons, FDC said.

“The department is currently accessing the facility for any damages that have resulted and have transported all the involved inmates to other locations. Additional information will be made available following a comprehensive after-action review and investigation,” FDC’s statement concluded.

The riot is the latest in a series of disturbances that have plagued the agency since January. Many institutions are at minimum staffing levels because of a shortage of corrections officers statewide.

The staff at Holmes, like many Florida prisons, has an abundance of young, inexperienced officers who have had little training.

“These officers are 19, 20, 21, some of them still live at home. They put them in charge of dorms for 12 hours a day with professional convicts, all by themselves,” said the officer. “I’m not a worrier but when you walk into those dorms you don’t know what you have or what they are going to do.”

Kim Schultz, president of the union representing the department’s officers, called the situation “extremely dangerous.” Florida’s state corrections officers are some of the lowest paid in the country, and they haven’t had pay raises in more than eight years, she said.

“This has resulted in high turnover and inexperienced officers who are not equipped to deal with prison riots,” she said.